One of the most overwhelming things we have learned from studying astronomy in the past century—and it’s quite a list—is that entire galaxies collide.

I cannot overstate how awe-inspiring that is. A galaxy is a vast thing: a self-gravitating collection of tens or hundreds of billions of stars, countless clouds of gas and dust massive enough to create billions more stars, and all of this (not including the dark matter, which we cannot directly see) spread out over 100,000 light-years—a million trillion kilometers.

By itself a galaxy is mind-crushing structure. But then to find that they can careen through space and physically collide with another such monster … it’s difficult to grasp the enormity of such an event.

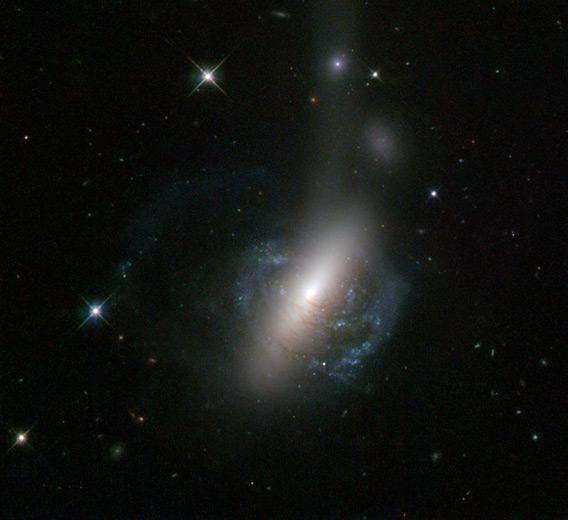

And yet collisions happen, and they happen often. And when they do, the result can be such beauty as to make even the most jaded cynic weep:

This is ESO 1327-2041, a pair of colliding galaxies located 240 million light-years distant from Earth, observed by the Hubble Space Telescope. One of the galaxies is a lenticular, a lens-shaped disk like a spiral galaxy without the spiral arms, and the other is a more normal spiral. At least, it used to be.

At some point, a few million years ago, the two galaxies first made a close pass, circled around, and then slammed into each other. It looks to me that the lenticular is passing right through the heart of the spiral, the two coincidentally centered on each other at the time we see this event, midcollision. The arms of the spiral wrap right around the lenticular, looking like a cosmic leukocyte about to engulf a marauding bacterium.

When galaxies collide, strange things happen. As they approach, the gravity of one pulls on the near side of the other more than the far side—that’s because gravity weakens with distance. The net effect is that the galaxies can get stretched out and distorted, and huge streams of stars can be drawn out or ejected from the parent galaxy.

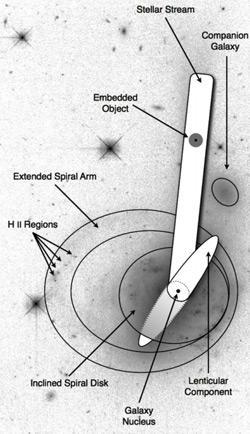

Illustration by Keeney, et al. from their paper.

Look again at the picture. See the long fuzzy streak going up out of the galaxies? That’s just such a star stream. But it gets better; the bright knot near the top may actually be the nucleus of the spiral galaxy, tossed out by the interaction.

I phrase that cavalierly, but it’s an event so powerful words are grossly inadequate. There are millions of stars in that glowing plume. Millions. That’s how much might is locked up in an event like this; the power to heave around entire stars by the millions.

It makes the hairs on the back of my neck stand up.

This collision is not done; eventually the two galaxies will merge completely, their material mixed, and they’ll join into one larger galaxy. All the most massive galaxies in the Universe have undergone this process at one level or another, growing into their enormous status by mutual cannibalism.

And after all that, amazingly, the collision pictured is not why those galaxies were observed using Hubble in the first place! It just so happens that there is a much more distant quasar coincidentally near those galaxies in the sky. Quasars are intensely bright galaxies, ones that have monster supermassive black holes in their cores, actively gobbling down matter, heating it up to fierce temperatures, and blasting out light across the electromagnetic spectrum.

The collision of the galaxies has tossed out a lot of gas, and that material is absorbing the light from the quasar. This type of absorption is interesting to astronomers; it’s like a fingerprint telling you how far the quasar and gas are. Gas that is otherwise dark between us and the quasar can be detected this way. Given that quasars can be seen from billions of light-years away, the Universe has given us a method to map itself for free.

That’s why astronomers pointed Hubble at ESO 1327-2041: It happened to be between us and a more interesting quasar. Until Hubble’s clearer vision was set upon it, the galaxy was thought to simply be a peculiar type called a polar ring galaxy.

Oh, how I love astronomy! One of the most powerful and awe-inspiring events in the entire Universe, the collision between two huge galaxies, and its true nature was only discovered by accident.

But once found, the astronomers looked at it on purpose to learn more about it, and surprises are part of the fun. It’s a big Universe, full of such delights, and there’s still very much left to learn about it.