Killing hashes

Like Nate Anderson's foray into password cracking, radix was able to crack 4,900 of the passwords, nearly 30 percent of the haul, solely by using the RockYou list. He then took the same list, cut the last four characters off each of the words, and appended every possible four-digit number to the end. Hashcat told him it would take two hours to complete, which was longer than he wanted to spend. Even after terminating the run two after 20 minutes, he had cracked 2,136 more passcodes. radix then tried brute-forcing all numbers, starting with a single digit, then two digits, then three digits, and so on (259 additional plains recovered).

He seemed to choose techniques for his additional runs almost at random. But in reality, it was a combination of experience, intuition, and possibly a little luck.

"It's all about analysis, gut feelings, and maybe a little magic," he said. "Identify a pattern, run a mask, put recovered passes in a new dict, run again with rules, identify a new pattern, etc. If you know the source of the hashes, you scrape the company website to make a list of words that pertain to that specific field of business and then manipulate it until you are happy with your results."

He then ran the 7,295 plains he recovered so far through PACK, short for the Password Analysis and Cracking Toolkit (developed by password expert Peter Kacherginsky), and noticed some distinct patterns. A third of them contained eight characters, 19 percent contained nine characters, and 16 percent contained six characters. PACK also reported that 69 percent of the plains were "stringdigit" meaning a string of letters or symbols that ended with numbers. He also noticed that 62 percent of the recovered passwords were classified as "loweralphanum," meaning they consisted solely of lower-case letters and numbers.

This information gave him fodder for his next series of attacks. In run 4, he ran a mask attack. This is similar to the hybrid attack mentioned earlier, and it brings much of the benefit of a brute-force attack while drastically reducing the time it takes to run it. The first one tried all possible combinations of lower-case letters and numbers, from one to six characters long (341 more plains recovered). The next step would have been to try all combinations of lower-case letters and numbers with a length of eight. But that would have required more time than radix was willing to spend. He then considered trying all passwords with a length of eight that contained only lower-case letters. Because the attack excludes upper case letters, the search space was manageable, 268 instead of 528. With radix's machine, that was the difference between spending a little more than one minute and six hours respectively. The lower threshold was still more time than he wanted to spend, so he skipped that step too.

So radix then shifted his strategy and used some of the rule sets built into Hashcat. One of them allows Hashcat to try a random combination of 5,120 rules, which can be anything from swapping each "e" with a "3," pulling the first character off each word, or adding a digit between each character. In just 38 seconds the technique recovered 1,940 more passwords.

"That's the thrill of it," he said. "It's kind of like hunting, but you're not killing animals. You're killing hashes. It's like the ultimate hide and seek." Then acknowledging the dark side of password cracking, he added: "If you're on the slightly less moral side of it, it has huge implications."

Steube also cracked the list of leaked hashes with aplomb. While the total number of words in his custom dictionaries is much larger, he prefers to work with a "dict" of just 111 million words and pull out the additional ammunition only when a specific job calls for it. The words are ordered from most to least commonly used. That way, a particular run will crack the majority of the hashes early on and then slowly taper off. "I wanted it to behave like that so I can stop when things get slower," he explained.

Early in the process, Steube couldn't help remarking when he noticed one of the plains he had recovered was "momof3g8kids."

"This was some logic that the user had," Steube observed. "But we didn't know about the logic. By doing hybrid attacks, I'm getting new ideas about how people build new [password] patterns. This is why I'm always watching outputs."

The specific type of hybrid attack that cracked that password is known as a combinator attack. It combines each word in a dictionary with every other word in the dictionary. Because these attacks are capable of generating a huge number of guesses—the square of the number of words in the dict—crackers often work with smaller word lists or simply terminate a run in progress once things start slowing down. Other times, they combine words from one big dictionary with words from a smaller one. Steube was able to crack "momof3g8kids" because he had "momof3g" in his 111 million dict and "8kids" in a smaller dict.

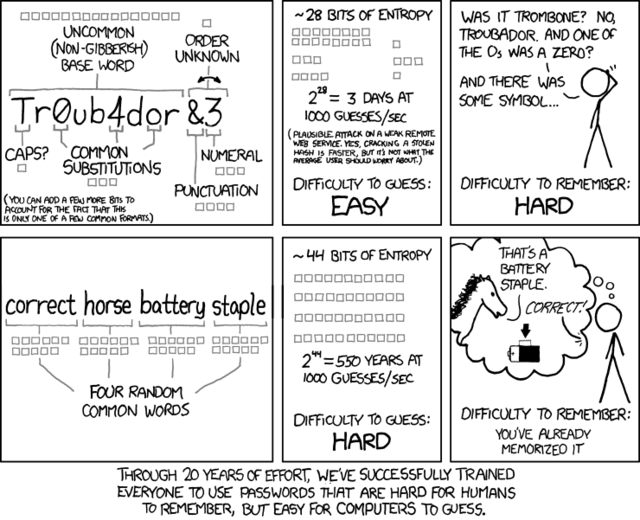

"The combinator attack got it! It's cool," he said. Then referring to the oft-cited xkcd comic, he added: "This is an answer to the batteryhorsestaple thing."

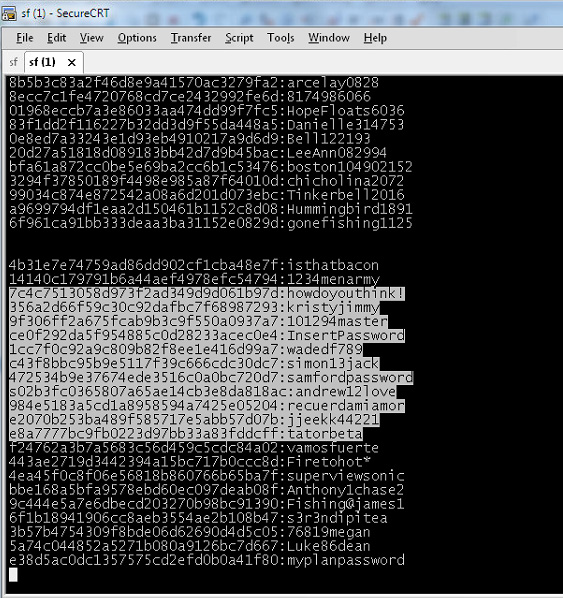

What was remarkable about all three cracking sessions were the types of plains that got revealed. They included passcodes such as "k1araj0hns0n," "Sh1a-labe0uf," "Apr!l221973," "Qbesancon321," "DG091101%," "@Yourmom69," "ilovetofunot," "windermere2313," "tmdmmj17," and "BandGeek2014." Also included in the list: "all of the lights" (yes, spaces are allowed on many sites), "i hate hackers," "allineedislove," "ilovemySister31," "iloveyousomuch," "Philippians4:13," "Philippians4:6-7," and "qeadzcwrsfxv1331." "gonefishing1125" was another password Steube saw appear on his computer screen. Seconds after it was cracked, he noted, "You won't ever find it using brute force."

The ease these three crackers had converting hashes into their underlying plaintext contrasts sharply with the assurances many websites issue when their password databases are breached. Last month, when daily coupons site LivingSocial disclosed a hack that exposed names, addresses, and password hashes for 50 million users, company executives downplayed the risk.

"Although your LivingSocial password would be difficult to decode, we want to take every precaution to ensure that your account is secure, so we are expiring your old password and requesting that you create a new one," CEO Tim O'Shaughnessy told customers.

In fact, there's almost nothing preventing crackers from deciphering the hashes. LivingSocial used the SHA1 algorithm, which as mentioned earlier is woefully inadequate for password hashing. He also mentioned that the hashes had been "salted," meaning a unique set of bits had been added to each users' plaintext password before it was hashed. It turns out that this measure did little to mitigate the potential threat. That's because salt is largely a protection against rainbow tables and other types of precomputed attacks, which almost no one ever uses in real-world cracks. The file sizes involved in rainbow attacks are so unwieldy that they fell out of vogue once GPU-based cracking became viable. (LivingSocial later said it's in the process of transitioning to the much more secure bcrypt function.)

Officials with Reputation.com, a service that helps people and companies manage negative search results, borrowed liberally from the same script when disclosing their own password breach a few days later. "Although it was highly unlikely that these passwords could ever be decrypted, we immediately changed the password of every user to prevent any possible unauthorized account access," a company e-mail told customers.

Both companies should have said that, with the hashes exposed, users should presume their passwords are already known to the attackers. After all, cracks against consumer websites typically recover 60 percent to 90 percent of passcodes. Company officials also should have warned customers who used the same password on other sites to change them immediately.

To be fair, since both sites salted their hashes, the cracking process would have taken longer to complete against large numbers of hashes. But salting does nothing to slow down the cracking of a single hash and does little to slow down attacks on small numbers of hashes. This means that certain targeted individuals who used the hacked sites—for example, bank executives, celebrities, or other people of particular interest to the attackers—weren't protected at all by salting.

The prowess of these three crackers also underscores the need for end users to come up with better password hygiene. Many Fortune 500 companies tightly control the types of passwords employees are allowed to use to access e-mail and company networks, and they go a long way to dampen crackers' success.

"On the corporate side, its so different," radix said. "When I'm doing a password audit for a firm to make sure password policies are properly enforced, it's madness. You could go three days finding absolutely nothing."

Websites could go a long way to protect their customers if they enforced similar policies. In the coming days, Ars will publish a detailed primer on passwords managers. It will show how to use them to generate long, random passcodes that are unique to each site. Because these types of passwords can only be cracked by brute force, they are the hardest to recover. In the meantime, readers should take pains to make sure their passwords are a minimum of 11 characters, contain upper- and lower-case letters, and numbers, and aren't part of a pattern.

The ease these crackers had in recovering as many as 90 percent of the hashes they targeted from a real-world breach also exposes the inability many services experience when trying to measure the relative strength or weakness of various passwords. A recently launched site from chipmaker Intel asks users "How strong is your password?," and it estimated it would take six years to crack the passcode "BandGeek2014". That estimate is laughable given that it was one of the first ones to fall at the hands of all three real-world crackers.

As Ars explained recently, the problem with password strength meters found on many websites is they use the total number of combinations required in a brute-force crack to gauge a password's strength. What the meters fail to account for is that the patterns people employ to make their passwords memorable frequently lead to passcodes that are highly susceptible to much more efficient types of attacks.

"You can see here that we have cracked 82 percent [of the passwords] in one hour," Steube said. "That means we have 13,000 humans who did not choose a good password." When academics and some websites gauge susceptibility to cracking, "they always assume the best possible passwords, when it's exactly the opposite. They choose the worst."

reader comments

493