The Duck Who Shared Her Eggs: How Children's Books Approach Modern Reproduction

As donors and surrogates make things potentially more complicated to explan, picture books remain eloquent ways of helping kids understand where they came from.

Behold the miracle of life -- the swimming sperm, the blooming cells, and quite often the parental dread when it's time to tell the kids how it all starts. Fortunately, picture books have long been around to ease The Talk, like Peter Mayle's 1973 classic, Where Did I Come From? which stars a rotund cartoon couple in the buff and clarifies that "vagina" rhymes with "Carolina." As in most such books of its ilk, the story essentially boils down to this: A man and woman love each other very much and lock genitals as an expression of their affection. Sperm meets egg and the woman's tummy grows until -- voila! -- a baby.

But what about children made otherwise? It's a serious question in the age of assisted-reproductive technology, especially for the burgeoning number of parents who use donor sperm, eggs, embryos, and gestational surrogates. As recently as a decade ago, a question that plagued many parents of donor-conceived children was whether or not to reveal their kids' true origins at all. Nowadays, with the stigma around donor conception fading as celebrities like Neil Patrick Harris and Sarah Jessica Parker speak openly about their egg donors and surrogates, and with recent research concluding that early disclosure is better for parents as well as for children, the primary question has shifted from one of "Whether or not?" to "When and how?" To that end, a new kind of picture book has emerged. In the past five years, nearly 100 English-language picture books have appeared to help teach the preschool set about donor conception.

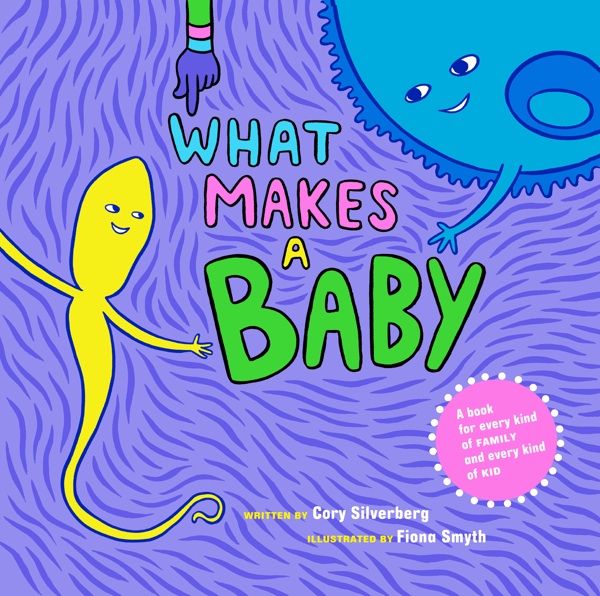

Consider What Makes A Baby, a book geared toward children aged three to eight. Breezing past any mention of men, women, penises, or vaginas, it instead features bright, genderless Keith Haring-esque figures and grinning Day-Glo sperm and eggs in a chirpy story about reproduction that's stripped to its minimalist core. "When grown-ups want to make a baby they need to get an egg from one body and sperm from another," it reads. "They also need a place where the baby can grow," it continues, with a picture of a bubblegum pink uterus so adorable one can imagine a furry stuffed version selling well. There's no explanation about how sperm and egg meet, only that they do, wearing red high-top sneakers and doing what looks like the Hustle. In the story, the union of gametes is equally as important as the loving arms of whoever eventually welcomes the baby. "Who was waiting for YOU to be born?" the book asks, a conversation prompter and parental tearjerker in one.

Cory Silverberg, a sex educator, was inspired to write "What Makes A Baby" for friends of his, a biological woman and transgender man who conceived their son with donor sperm, and he intentionally crafted the story so that parents of any gender or sexual identity who conceived with any type of reproductive assistance can incorporate their own details (an accompanying reader's guide offers advice on how to do so). Enthusiasm for the book seems to underscore the demand for such inclusive baby-making tales: Silverberg launched a Kickstarter campaign last year to raise to $9,500 to self-publish it, and within a month, his fundraising video had gone viral and the project garnered $65,000. The book's initial printing of 4,000 copies sold out quickly and he subsequently signed a three-book deal with Seven Stories Press, which is republishing What Makes A Baby next month.

"My hope is that kids get something about the unique story of how they came to be born, as well as something a bit more universal," Silverberg said. "One thing that's true for everybody is the biological piece of sperm, egg, and uterus. And when you take intercourse out of the center of the story, it says, 'That's not the normal way. It's one of many ways.'"

Other picture books are specific to certain types of donor-assisted reproduction. In Mommy, Was Your Tummy Big? by Carolina Nadel, an elephant couple bereft that they can't have a baby are introduced to another elephant in a wide-brimmed sunhat who gives them the gift of an egg, which is mixed with the daddy elephant's cells and implanted in the mommy elephant's belly. Egg donation gets a similar treatment in The Very Special Ducklings, by Wava Cirisan, which tells of an especially fertile duck who generously gives two eggs to her friend, who could lay none.

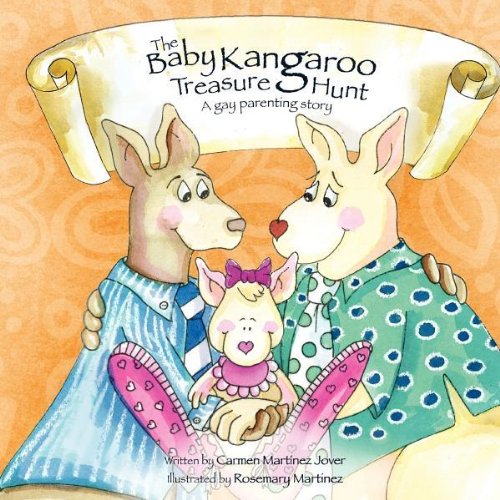

The menagerie expands in books about surrogacy, like The Baby Kangaroo Treasure Hunt, by Carmen Martinez Jover, which frames the fatherly yearnings of a gay kangaroo couple as an adventure, challenging them to retrieve special seeds from one female kangaroo and find another to loan them her pouch. The same pouch-sharing idea drives the narrative in Surrogacy, A Magical Delivery by Tamara Martin, but this time starring a cute family of opossums.

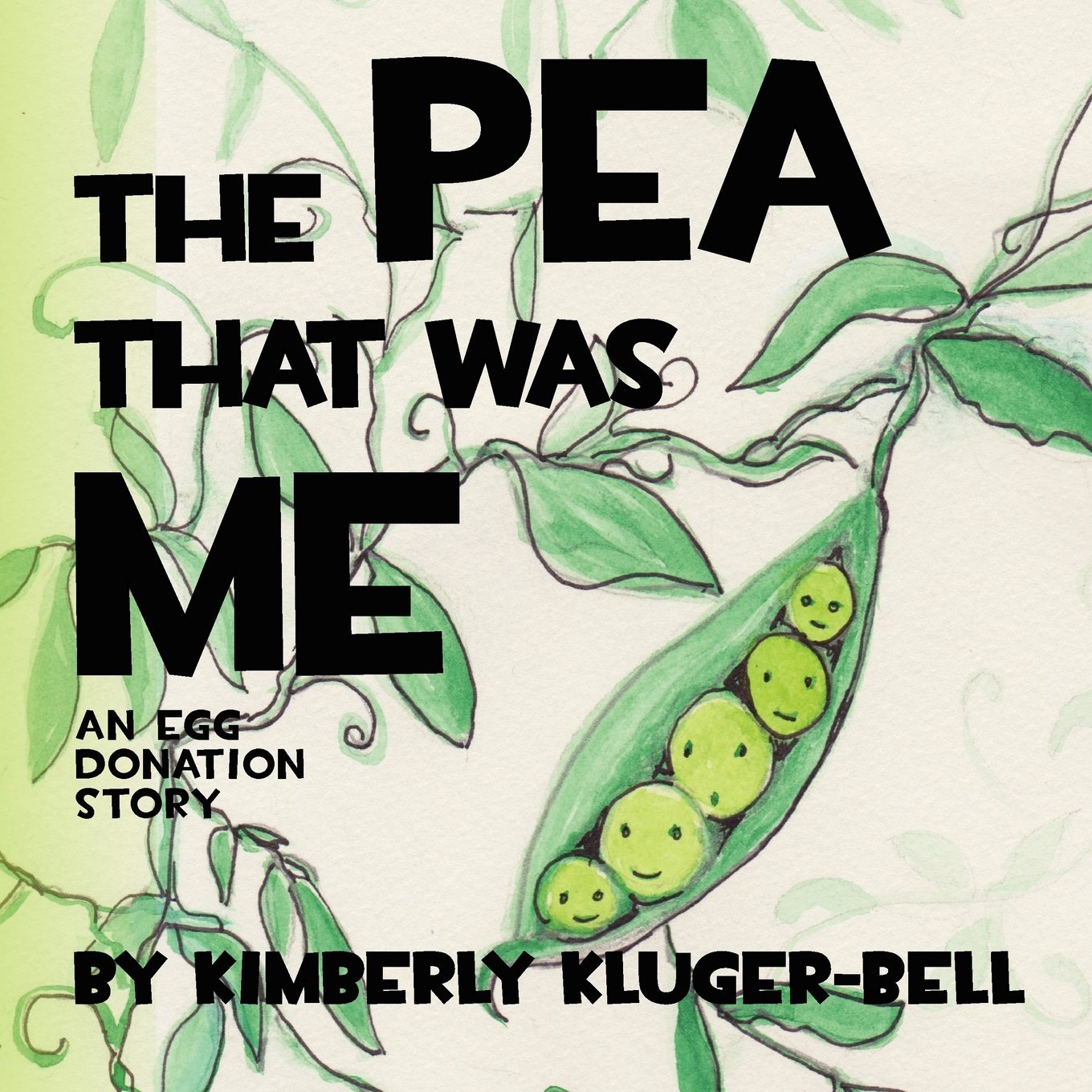

Not all the books are zoologically oriented -- many feature human subjects and basic explanations of how assisted reproduction really works, like The Pea That Was Me, by Kimberley Kluger-Bell, a story about sperm donation as explained to a three-year-old, and Nan's Donut Dilemma, by a Mary E. Ryan, in which a single mother explains to her daughter how "Doctor Deb and a man we've never met helped me have you."

The trend has not gone unnoticed. Three years ago, Patricia Sarles, a school librarian, and Dr. Patricia Mendell, a therapist specializing in fertility issues and alternative family building, published an article about the phenomenon, "Where Did I Really Come From?" in the journal Children & Libraries, which led to calls for the Library of Congress to create a new subject heading for children's books about donor offspring. (The call was partially satisfied last year with the creation of a subject heading for children's books about sperm donors, although advocates hold out hope that a subject heading will be created that encompasses all manner of donor conception.)

Dr. Mendell, who has also authored parents' guides on talking with children about sperm and ovum donation, endorses early disclosure not least because secrecy, she believes, poses far more harm to the parent-child bond than the absence of a genetic link. Still, she recognizes that it's not an easy topic to broach.

"Part of the problem is, how do you begin?" she said. "The picture books are a nice way of beginning. People always think children process the same way you process, and they don't. Their cognitive abilities are very concrete. Even if you just read these as stories about how people help other people, people share, or people see other people in trouble, stories are the way in which you make connections."

In that respect, picture books about donor offspring are not so different than picture books that parents have long used to broach all kinds of sensitive issues, from adoption and new siblings to death and divorce. Within the refuge of a story, picture books render the strange as familiar and shape the chaos of life into meaningful forms. They plant the seeds for children to understand that their personal stories are not theirs alone.

For parents of donor-conceived kids, these books are a welcome comfort as such. And ultimately, they impart the most important lesson of all. Like the duck sharing her eggs or the kangaroo loaning her pouch, someone may have contributed something special to spur their child into existence. But in the end, children learn, it's their parents' love that really makes them.